Kinship Realism: Tribalism Forever

A new form of social science

Why does Scotland still vote along the borders of its Iron Age kingdoms?

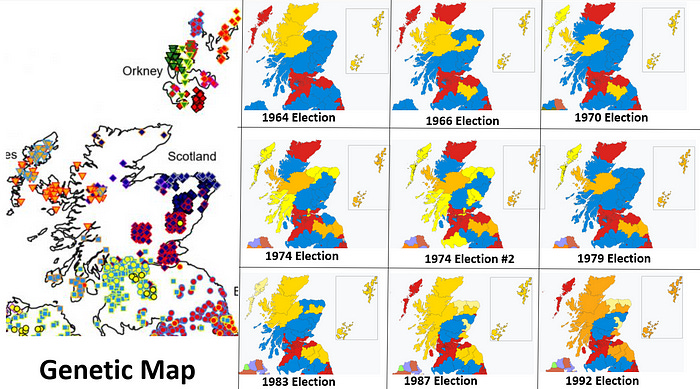

I first noticed the pattern when reading Jim Wilson’s work mapping the genetic landscape of the British Isles. His team found, by looking at Scots with ancestry from particular regions, that the country is still genetically divided along the borders of the old kingdoms of Pictland, Strathclyde and others. Wilson’s genetic maps look startlingly similar to Scotland’s electoral ones.

It’s one thing to not move around much, and who could blame you in that climate, but why would the modern inhabitants of these ancient kingdoms also vote along those lines? As a part Scot myself I’m open to the idea that we’re uniquely tribal savages, but there appears to be something driving this that applies universally, something that may fundamentally change the way you view the world, dear reader.

Consider the graphic below. On the left, you see genetic clusters mapped near the ancestral homes of those who volunteered their genomes for study. On the right is a selection of UK Parliamentary election results.

Genetic map of the British Isles based on work by Professor Jim Wilson from the University of Edinburgh’s Usher Institute and MRC Human Genetics Unit (source) alongside voting data.

A keen eye will notice that when the clusters are mapped to the Parliamentary constituencies, they appear to choose different Parliamentary parties to their neighbouring clusters. Indeed, over the sample period most of the time clusters voted differently to their neighbours regardless of the party in question.

Number of times a genetic cluster voted differently to most of its bordering neighbours (excluding cities) in general elections over 1964-92

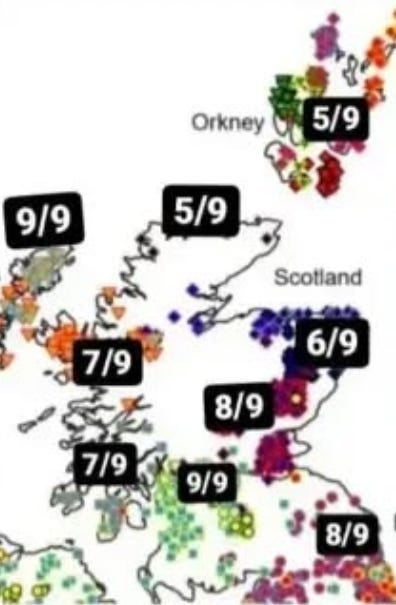

This phenomenon is also visible on a wider scale. Callaway’s genetic map of the rural UK (source) based on those with four grandparents from a particular area closely resembles the 2017 electoral map, and many others before and since.

Callaway et al. (left), BBC (right)

Northern Ireland is of course known for its sectarian conflict, and the division of votes along ethnic lines is not surprising there. Such division is not widely consciously practiced in the rest of the country, however. Yet here it is, in plain view. Staunchly Labour-voting North West England is revealed to be inhabited by a genetic cluster distinct from the Tory-voting Home Counties in England’s Southeast for example. Likewise, Northumberland maintains itself as distinct both politically and genetically. While the sample for Brighton was small, Callaway’s study picked up a Devonian cluster around the city, which prides itself on voting Green as distinct from the traditional conservative heartland surrounding it. The Cornish independent streak is visible on older electoral maps, but its recent lack of political distinction in general elections has coincided with increased settlement of English internal migrants from the 20th century, reinforcing the idea that voting still occurs along genetic lines.

Bring Back Biology

The most parsimonious explanation for this phenomenon is rooted in our biology. Culture, economics and all the social sciences offering explanations for political phenomena are determined by the limits set by the harder sciences. To study human behaviour, we must understand humans.

Like any other creatures, humans have evolved to favour genetic relatives as well as ourselves as individuals. There is a simple logic to this: our genes don’t need to be present in us individually to propagate. If the same genes present in us are present in our relatives, it makes sense from an evolutionary perspective to behave altruistically towards those relatives to keep our genes alive. Geneticist J.B.S. Haldane encapsulated this idea in his quip that he would lay down his life “for two brothers or eight cousins”.

This logic of genetic altruism holds for groups of those similar to us too, though the precise mechanism of how this happens beyond the extended family is still debated. Rather than laying down your life, it may make sense to sacrifice one vote and choose a candidate favoured by the extended kinship group rather than the political candidate most aligned to your political principles in order to benefit the wider group and make survival of your genes more likely. Ethnic nepotism in voting can be genetically beneficial to the in-group you share genes with by directing more resources from the governing body towards those more likely to be related, and helps maintain your cluster of genes’ distinction from other genetic groups in competition.

This competitive alliance system does not require that the groups be formally discussed. Due to the influence of genes on phenotypes, genetically similar people recognise each other as part of an in-group unconsciously, without having to vocalise a shared identity. This perception of similarity to oneself is a cue of kinship, and would be sufficient within the social contexts that emerge in larger groups to give preference to more related people in political alliance formation.

When applied to politics and warfare, I call this analytical approach kinship realism. In international relations theory, realism purports that nation states act independently in their own self-interest, forming and dropping alliances as they go. I propose that kinship groups act in this manner in the political realm, prioritising their own genetic interest above those even of their countrymen from rival clusters.

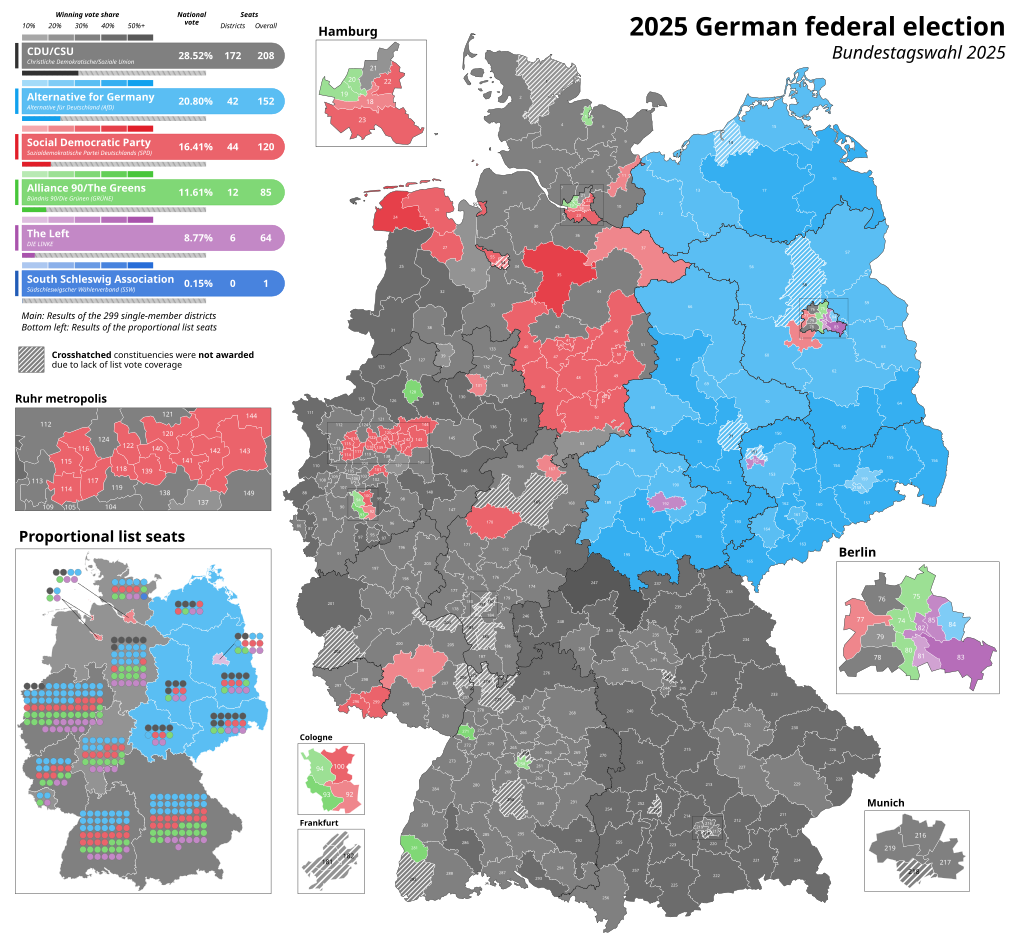

Let’s apply this kinship realist framework to one of the great political issues of our day: the rise of the German “far-right”. As in Scotland, the voting appears to be concentrated along ancient political lines. The much-maligned AfD does well in the historically Slavic regions of East Germany.

German 2025 Federal election results mapped by Wikipedia, showing AfD winning in East Germany.

Ancient Slavic tribes mapped by Wikipedia, showing East Germany inhabited by tribes not present outside of AfD-voting regions.

The lands formerly inhabited by the Sorbs, Obodrites and Veleti still contain direct descendants of those tribes. The genetic signal of those ancient Slavs is present more in East Germans than West today, even outside of the modern Sorbian population that maintains a distinct language and culture. Simply put, a kinship realist approach would predict that East Germany should vote distinctly to the rest of Germany. The rise of the “far-right” appears instead to be the rise of Slavic Germany limited to its traditional homelands.

Kinship Lives

Humans have no overriding reason to behave fundamentally differently to how we have done since time immemorial. Why shouldn’t the Scots still be tribal? Why shouldn’t East Germany organise along ancient genetic lines without announcing it to the world? Being as we are, could we ever behave differently?

Charles Small is an open-source intelligence consultant. Get in touch for a consultation: charles@csmall.co.uk

Please donate to support my research: https://buymeacoffee.com/csmall

Can attest. Born in Stornoway, grew up in Strathclyde, educated and worked in Aberdeenshire, and I live in Lothian now. I have long said, Scotland is really 8 nations who think the other 7 are just not as 'Scottish' as they are.

It is! The Iberian Peninsula has clear divides, but as there's a linguistic split as well I chose Scotland, which is less divided in that respect. France too to some extent, and Poland (Kashubains/Pomeranians, Silesians and other Poles tend to vote differently). I've expanded on it a little here:

https://www.aporiamagazine.com/p/ethnic-tribalism-in-politics