Kinship Realism: Do Non-English Rulers Import More Immigrants?

Using genetic distance to predict immigration policy

A common motif in British media is that of the immigrant origin politician claiming to want to crack down on immigration. While the newspapers express outrage at the rise of the new far-right, native voters often express cynicism: would someone so obviously not of their ethnic stock protect Britons’ dwindling grasp over their ancestral homeland?

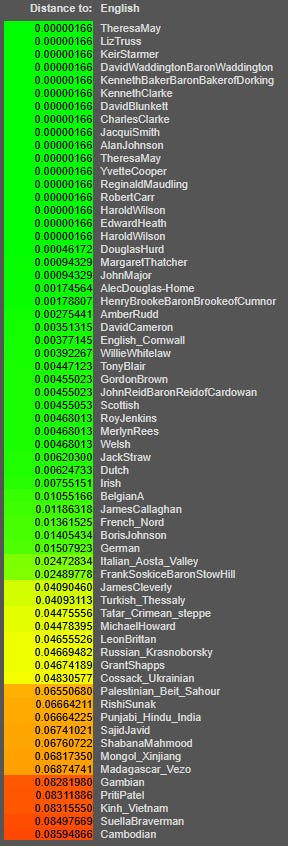

To investigate this, I plotted the estimated genetic coordinates of Prime Ministers and their Home Secretaries from 1964 to 2025, then measured the distance between them and the average English person using Global25 coordinates, and compared this to UK immigration numbers, being overwhelmingly to England.

Approximate genetic distances of Prime Ministers and Home Secretaries over 1964-2025 from the English reference coordinates used in calculations, with comparably distant populations

The Threshold Effect

Given bureaucratic inertia and the fact that immigration statistics are imperfect estimates, even if genetic distance did explain immigration numbers, we would not expect a perfectly linearly correlated relationship. The pattern of immigration’s rise over the observation period suggests that explanations framed purely in terms of short-term demand are incomplete. Immigration advanced in steps, settling onto higher plateaus which then persisted. To analyse these potential regime-level shifts, I measured whether changes in genetic distance were associated with deviations from a rolling average of immigration over the previous three years.

Net immigration shown with Prime Ministers’ and Home Secretaries’ genetic distance to the English reference population over 1964-2025

Overlaying the average full year genetic distance of Prime Ministers onto this series produces a striking alignment. Periods in which Prime Ministers were genetically closer to the English reference tended to coincide with lower immigration levels. This relationship survived controls for time, and years in which immigration significantly exceeded the recent baseline were more likely to coincide with Prime Ministers who were genetically more distant from the English. This is consistent with the idea that leadership alignment matters most at moments of regime change, when new defaults are being established, rather than during steady-state management.

The role of the Home Secretary was more ambiguous. While Home Secretaries clearly matter operationally, their genetic distance did not show the same stable relationship with immigration outcomes once broader regime context was taken into account. This is not especially surprising. Home Secretaries operate within constraints set by the governing regime, administering a bureaucratic machine with a direction largely having been fixed elsewhere.

The relationship between gross immigration and Prime Ministers’ genetic distance from the English was non-linear. Instead, the relationship appears to behave more like a threshold. Below a certain boundary of foreignness from the English, more foreign leaders tended to import more immigrants, and once crossed, additional genetic distance added relatively little explanatory power. The genetic distance threshold which best fits the data is around 0.004 in the Global25 space, roughly the distance between Cornish and English people. While David Cameron is just about as foreign to an Englishman as a Cornish person, Boris Johnson for example is about as genetically distant from an Englishman as a baguette-munching Parisian is. Statistically, much of the explanatory power of this is due to more recent leaders being much further away from the English, while they have increased immigration.

This threshold behaviour is what one would expect if the mechanism at work is based on an in-group, out-group distinction. In most social contexts, the largest shift occurs when someone is no longer perceived, consciously or unconsciously, as part of the in-group. Beyond that point, further distinctions matter less.

Average genetic distances of immigrants, Home Secretaries and Prime Ministers to English reference, and a multiple of immigrant genetic distance by immigrant numbers over 1975-2019

A separate analysis of genetic distance of immigrants themselves shows significant changes over the observed 1975-2019 period. More genetically distant Prime Ministers not only imported more immigrants, but they also tended to import immigrants who were more genetically distant to the English than those previously imported. While the data from 2020 onwards are not directly comparable due to methodological changes, this pattern appears to have held until the present.

The Persistent Scottish Raj

Placing these findings into historical context strengthens the interpretation. New Labour taking power in 1997 marked a clear political transition. Under what was known as Prime Ministers Blair and Brown’s “Scottish Raj” rule until 2010, the immigration and asylum system was repeatedly restructured through major Acts, beginning with the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 and continuing through the early 2000s, opening up the country to mass immigration. One of Blair’s speechwriters Andrew Neather claimed that this was politically-motivated, to “rub the Right’s nose in diversity”, meaning in practice to introduce large populations of other ethnic groups into Anglo-Saxon areas, triggering mass informal evacuations of urban environments known as “white flight” and local minoritisation of those remaining.

In 2004, a structural break occured with EU enlargement. The UK’s implementation choices determined how this expansion translated into actual population flows. Blair, who despite his English admixture is effectively as foreign to an Englishman as a Scotsman, chose to ramp up immigration from the enlarged EU in 2004 despite having the power to postpone immigrants’ access to the UK for several years instead. Then, in 2008, the Points Based System was rolled out through changes to the Immigration Rules, further entrenching the new baseline. Throughout this period, Home Secretaries changed, but the overall direction remained consistent.

Then, from 2014 onwards, the focus shifted toward internal enforcement and access to services. This phase was often described as a clampdown, but did not reverse the earlier step changes. When Boris Johnson took power as Prime Minister in 2019, a leader as foreign to the English as a Frenchman oversaw the implementation of a new post-Brexit immigration regime and historic records of immigration known as the “Boris Wave”, with historically high numbers through the brief Truss and longer Sunak premierships until Starmer took over in 2024 and numbers appear to have falled back down again.

Taken together, these results do not prove that Prime Ministers’ genetic distance causes mass immigration, or disprove the importance of economic conditions, international obligations, or institutional inertia. What they do suggest is that Britain’s immigration system has been defined by institution of regimes, and that the genetic distance from the English of those in power during the establishment of new regimes may influence persistent levels of immigration.

So when natives express scepticism that leaders who are clearly not of their ethnic stock will act to preserve the demographic status quo, are they merely indulging prejudice, or are they responding to a real pattern? The evidence suggests that their intuition has been grounded in something observable.