The Government's Men

What are they doing in the woods?

Who are the government's men in the woods, and why did the government put them next to the children’s play area?

These questions are loaded with assumptions, showing us how framing of popular concepts can influence our perceptions. By “the government's men in the woods”, I am referring to the 146 migrant men installed by the Home Office in a large hotel in Peterborough's woods, located next to a children’s play area, close to primary schools and with direct access to two military bases from the bus stop a couple of minutes’ walk from the door. This is a propagandist’s dream, but in the state media-dominated UK, the government often has first-mover advantage and channel dominance.

It is an open secret that we are nudged and subconsciously coerced into viewing politically sensitive issues in certain ways by information warfare techniques deployed by a small clique of propagandists, including the famous Nudge Unit that grew out of the Cabinet Office and other units in the Home Office and other departments. What’s missing is a proactive counterbalance to this in the private sector. There is a loosely aligned vanguard of op-ed writers, pseudo-independent think tank personnel and video commentators across the media ecosystem, but no core of media planners operating organically at the proficiency level of a government communications unit. This is a drawback, but also an advantage, as it is worth assuming that any such political organisation will be subverted through infiltration or otherwise influenced heavily by the state to the point of ineffectivity.

As the UK information environment develops, how are politically active people likely to organise to resist the information warfare efforts of the government’s clique?

Such movements typically use a mixture of formal and informal organisational tactics to resist governments, with a core organisational structure around which ideas and people coalesce. Much as the communist vanguard would discuss policy at London pubs during the Bolshevik-Menshevik split after their congresses were banned in Europe, nativist movements in the UK tend to have to keep venues secret until the last minute to prevent disruption by state-affiliated media and activists on the Home Office’s payroll lobbying to close their events down, with some event organisers abandoning London altogether in favour of European host countries. Such political activism will likely continue to require flexible organisational behaviours domestically. With the rise in political persecution through the UK’s speech restrictions, several activists currently live in de facto exile in Europe due to likely arrest on arrival if returning to the UK, creating the potential for a more stably organised nationalist hub beyond the reach of the state.

Social media sites are currently a primary method of such informal organisation, though such venues are most at risk of subversion by UK and other government actors. Messages are passed between users in digital bottles floating in a sea of messages from information warfare accounts run domestically, by other militaries directly or by outsourcing to marketing agencies running bot accounts out of Nigeria, the Philippines and other low-cost markets. For every authentic public message a member of the political vanguard receives on X, there are accompanying comments and elicitation statements from militaries actively trying to subvert political activity. Frankly, the potential for immediate reach, perhaps enhanced by a journalist reading the message floating by, mixed with the addictive intermittently-reinforced dopamine hits from notifications, makes social media likely to continue to be preferred in spite of the vulnerabilities.

Outside of formal events and social media, decisions on policy direction and how to communicate new ideas to the public to advance political causes will likely be made at otherwise unassuming social events, now rather less excitingly mixed with group chats and video calls, rather than requiring anything close to the organisational resources of the state.

Concept Fusion and Small Boats

And how could this currently loosely-organised vanguard overcome the state’s information warfare efforts to enact political change?

Returning to the idea of “the government's men in the woods”, this phrase presents a simple link in the reader’s mind between migrants and the UK state. Neurons that fire together really do wire together, and the simple act of labelling the men in this way strengthens the physical connection in the reader’s mind between thoughts of the government and the sinister vision of the unknown men near children in the woods. The more often concepts are expressed at the same time, and the stronger the emotional context, the better people recall associations.

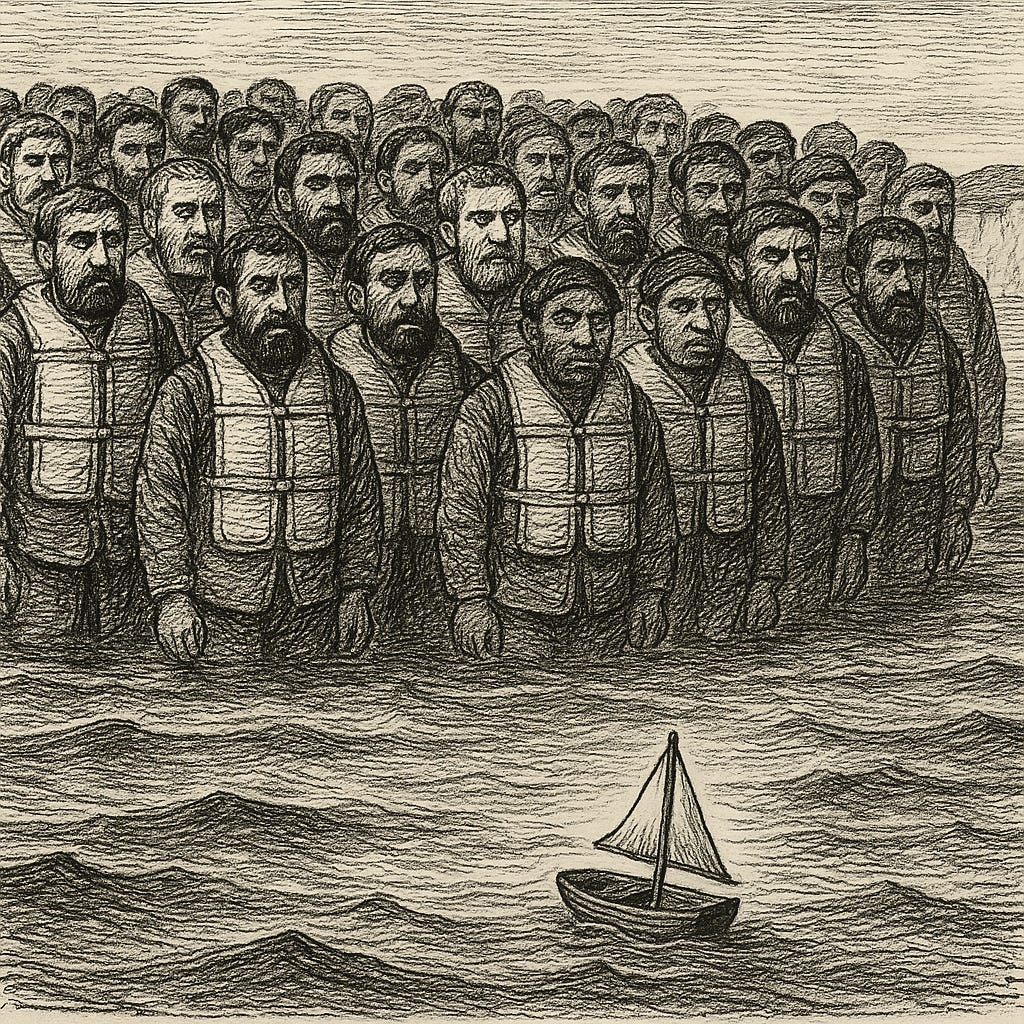

With this in mind, consider the recent use of the term “small boats” to refer to the large-scale Channel migrant crossings. The term, used across state media channels, is perfectly suited for state propaganda. Firstly, it takes the focus off the men in the boats by not even mentioning them. Much effort has been made to suppress news of the men arriving across the Channel over the years, including building a walled walkway on the shore to obstruct photography, and state media until recently almost never showing pictures of the men arriving, only the much rarer images of women and children. The absence of the men from this term can be seen as a part of that.

Secondly, the diminutive “small” shrinks the concept in a person’s mind. In neurolinguistic programming, it is common when considering a problem to visualise it then shrink what is visualised in the mind’s eye. One common example is imagining that critics are small dogs yapping, becoming smaller and quieter. Focusing on boats also minimises the overall scale of the crisis, as people would not commonly visualise the arrival of tens of thousands of people when thinking only of the boats. The state's use of this term encourages acceptance of the government policy to transfer large numbers of illegal immigrants into residential areas. The political vanguard do not, of course, have to use it.

What good is a platform if you’re unable to speak?

French academic Renaud Camus was recently banned from entering the UK due to his discussions of the Great Replacement, a concept the state has expended a lot of effort to stamp out. There remains no politically acceptable way in mainstream media of describing the displacement of many millions of Europeans and the importation of millions of non-Europeans to live in the homes they have abandoned. The concept has simply not been allowed to be exchanged freely, as the state has the resources of its political police, with significant support from American, European and other security forces, to restrict the flow of ideas at home through censorship. This has included pressuring social media platforms into soft censorship, detention and court-mandated silencing of political activists. There is therefore an asymmetric balance of power in the battleground of ideas.

With the loosening of censorship on X and recent pivot of the US government, the tide appears to have turned, and ideas are now floating into mainstream discourse. While the state may still detain political vanguard members for causing offence on the platform, its censorship operations are far less restrictive than even a few years ago. This opportunity to exchange ideas has been seized on, with the new concept of the Yookay used to label the degraded shadow of what the UK once was being a prime example, and the US State Department openly discussing population displacement in Europe.

So what about the small boats?

While I do like my surname Small, a competent activist would outright refuse to use the term “small boat” in this context. The obvious choice would be to call it an “armada”, a word with salient historical meanings for the British, associated with a foreign force invading. A multitude of other words could be used alongside it, but when competing with state propaganda it pays to be pithy and consistent. Calling it the “paedo armada” or “rape armada” based on the high number of sex offenders the government brings into the country via this route is emotionally salient, but unlikely to be oft-repeated in the press. Calling it the “government’s armada” or “traitors’ armada” emphasises who is responsible for this - it is government policy to bring these men into the country and put them in the woods next to the children’s play area. Calling it an invasion separates it from the state, as if it wasn’t caused by government policy intentionally.

The most effective approach would be to think strategically about which concepts activists wish to be associated with the regular outrages of the migrant crisis. Fusion of the concepts of mass immigration and the government would likely enact change most rapidly by degrading the reputation of the state.

Let’s consider the potential impact of using the term “the government’s men” instead of “small boat migrants”. Repetition of the term in every child rape or murder headline, which appear in the news near-daily, would suddenly drive home the fact that the state is importing people en masse who as a group frequently carry out atrocities against the population of the UK. The “small boat” framing positions the headline reader beside the UK government looking across the Channel at tiny boats floating far away, whereas the “government’s men” framing positions the reader as being confronted by an alliance of both the state and the migrant settlers, far more emotionally salient.

Until the UK’s political vanguard take an active interest in information warfare techniques, the state’s clique will continue to dominate discourse. For now, I still wonder what the government’s men are doing in the woods.